The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the most rapid and profound transformation in healthcare in many healthcare professionals’ careers. The crisis has changed their teams, their relationships, and who they are.

The approach has shifted from “me, myself and my patients”, to “we’re all in this together.” Within a week, primary care practice has changed from exclusive face-to-face meetings to about 95% telephone consultations. Accessibility — an intractable problem in Canadian primary care reforms over the past 20 years — increased markedly within a few days. The “bureaucratically frozen public health system” has thawed, and massive improvements have been achieved without adding a single professional. Hierarchies have been shaken and people have mobilized the intelligence and creativity of the whole team to transform the way they work together. This team includes receptionists, cleaning staff, equipment suppliers, and managers as well as hands-on health professionals.

The immediate tragedy happened mostly in uncontrolled outbreaks in long-term care facilities for the elderly where 80% of deaths were concentrated and it was difficult to provide basic care due to staff shortages. Limited visits from family and loved ones compounded the experiences of grief, suffering, and anxiety relating to those deaths. At the community level there were looming long-term challenges relating to the health, social and economic impacts of the pandemic, including unemployment, isolation, and untreated long-term conditions in the areas of cancer, heart disease and mental health.

“New” technologies (i.e. telephone, e-mail, and the internet) were rapidly adopted for prescribing, document exchange, and video conferencing. Healthcare professionals were suddenly questioning the value of every diagnostic test, referral, and treatment, asking if their interventions do more harm than good (e.g. balancing the risk of in-hospital investigation for chest pain in people at high risk of Covid complications, in view of that day’s local epidemic data).

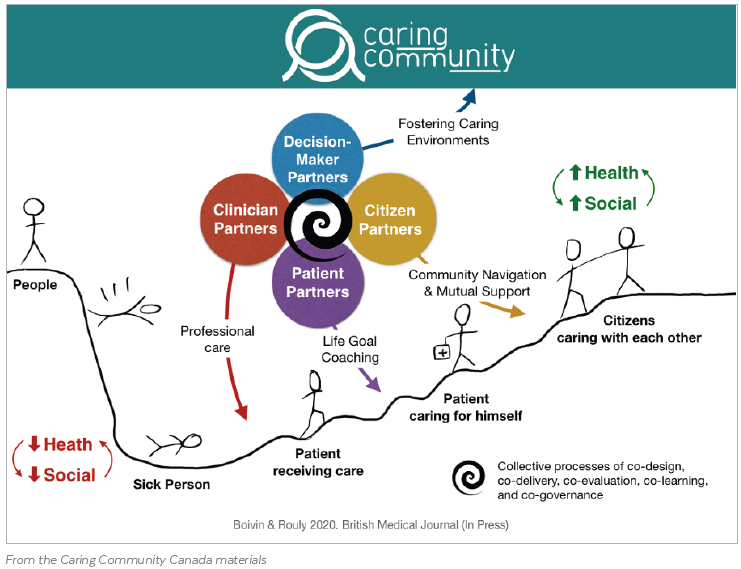

The pandemic made many people realize that patients, citizens, and community members can be trusted as caregivers. Mothers and fathers have become the doctors’ eyes and ears when assessing a child’s illness over the phone. The majority of patients with Covid (and other conditions) have been caring for themselves, by themselves, at home, with help from neighbours, family, and friends.

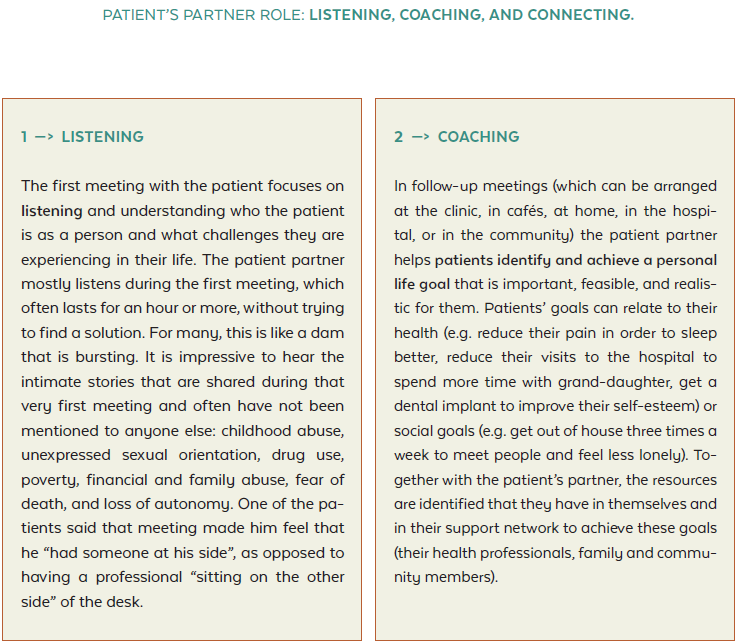

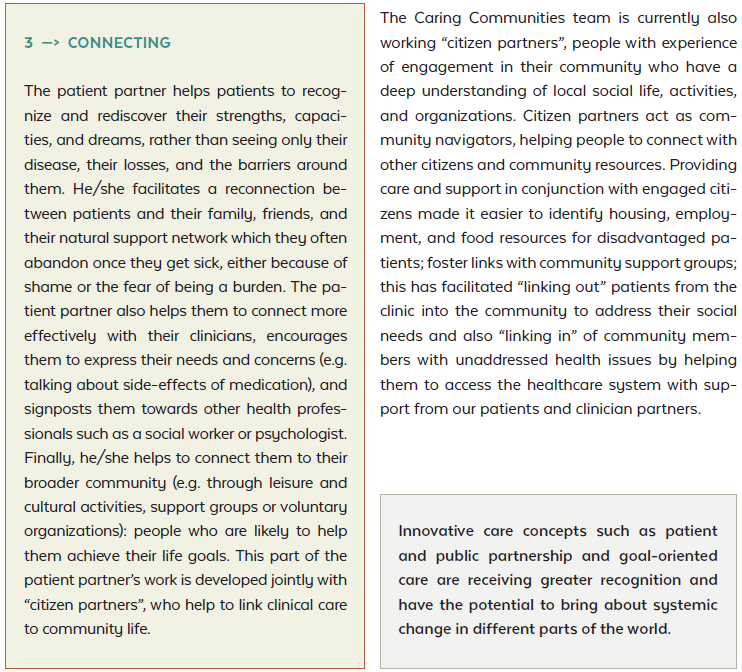

Doctors were impressed by how resilient many of their patients are. They embraced change, offered constructive suggestions and mobilized their knowledge and inner resources to adapt to the crisis, showing appreciation and being reassured by the ongoing connection with a trusted team of health professionals who know them. Experienced patient partners working closely with the primary care team coached and supported other patients to help them find practical solutions in new situations.

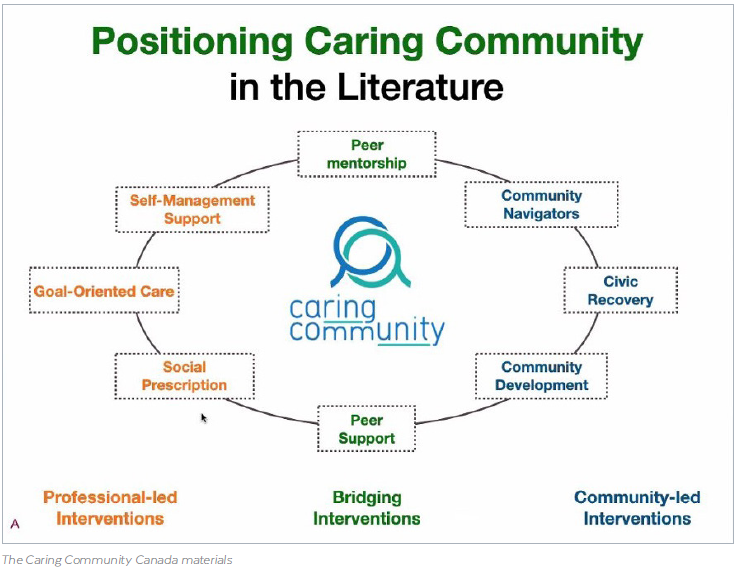

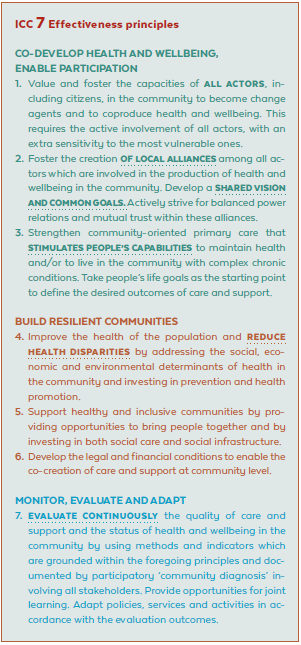

People who were already working together in theory have become real partners, as community organizations and health professionals seek joint solutions to common practical challenges. Volunteers of all ages (children, teenagers, adults, and seniors) have alleviated the health impacts of social isolation by maintaining contact with people confined at home. Community organizations, peer-support workers, social care, and volunteers were acknowledged as key players in addressing huge needs in the areas of psycho-social, practical, food, and economic support. Local initiatives came into being in the health care system and local authorities to meet the needs of the most vulnerable individuals in communities (e.g. turning old buildings into individual rooms to provide home isolation for homeless people). Professional turf wars have been abandoned as people realized their inter-dependence with colleagues working in intensive care units, hospitals, emergency rooms, other primary care clinics, home care, long-term care, palliative care, public health, not-for-profit community organizations, and informal social support networks.

Suddenly many people realized the common vulnerability of being at risk of illness and death. Everyone was deeply reminded of their interdependence and personal need for support. At the same time, many people have become much more aware of their privileges. There is a feeling that we are all in the same boat, but not all of us have access to lifeboats. “Health inequalities” and “social determinants of health” have changed from abstract concepts to real patients, friends, and community members who have fallen ill, lost their jobs, been unable to pay for rent or groceries, lived alone or been unable to implement “home isolation” because they had no home or were living in crowded shelters or on the streets.

There is also a strong feeling that the choices now being made are likely to shape individual and collective futures.

The focus in the Caring Community project has been on three things:

1. Linking people with community care to address Covid-related and non-Covid related health care needs.

2. Facilitating bonding among community members to facilitate mutual support with day-to-day activities, groceries, communication needs, etc.

3. Building bridges with community support organizations to ease the psycho-social impacts of the pandemic.

Since primary care facilities have practically emptied and staff have been redeployed, patients were reluctant to seek consultations. Consultations dropped by 50%. The Caring Community therefore had to switch from reactive to proactive care. This meant pulling up a list of patients and calling those who were most vulnerable, or working with communities and experienced patient partners who could proactively call people and find out their current needs. At present these include dealing with the consequences of social isolation and practical issues (including groceries), but also letting all patients know that there is still a team behind them if they need it.

A stronger sense developed that doctors are both caregivers and care recipients, that they need to care for one another. Health professionals are vulnerable and need to be supported but can also provide care beyond their role as health professionals. They are part of the community they serve. They are on the same team. What will most likely remain after the pandemic is a changed sense of distance and proximity. There is a new sense of the importance of neighbourhoods. Support networks exist in proximity, but those who are far away can also come closer, when people around the world can be gathered more easily. There is a changing idea of what is close and what is far away — how can we provide support to those who are physically distant from us?