CHC Botermarkt

It was the second CHC opened in Flanders (Belgium) founded in 1978. It provides primary care for the people living in the southern part of Ghent. It employs 10 FTE GPs (General practitioners), 10 nurses, nurses, 2 social workers, one heath promoter, dentists and psychologists, circa 50 people altogether. The Botermarkt Community Health Centre currently serves circa 6000 patients and that is the capacity limit (both from the location and number of staff perspectives). The CHC is financed by an integrated needs-adjusted interprofessional capitation, without co-payment for the patient.

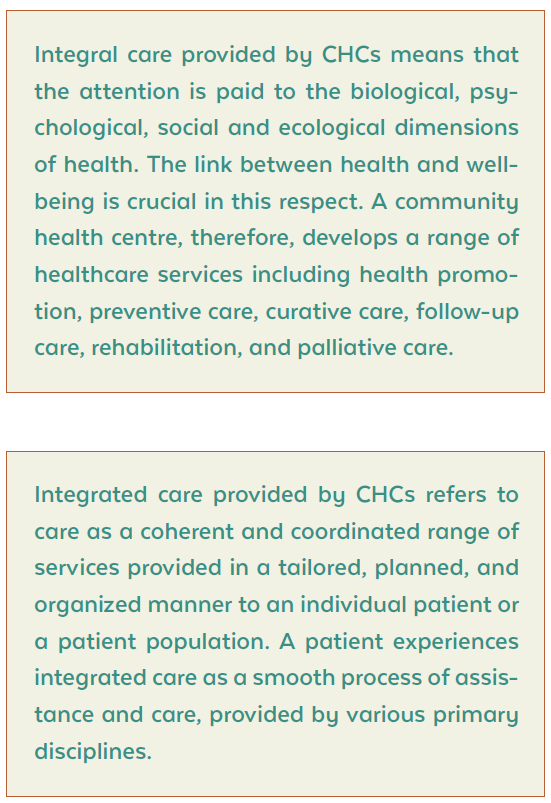

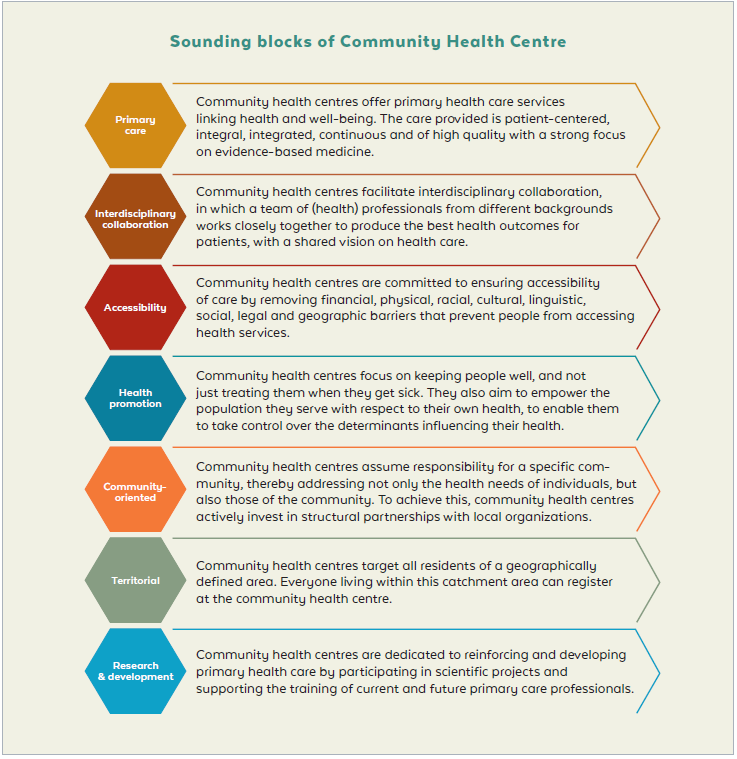

CHC Botermarkt provides high-quality, accessible primary health care for all residents of Ghent South, Ledeberg, part of Melle and Merelbeke. It contributes to an open, solidarity-based, just, and sustainable society with attention to diversity in all its aspects.

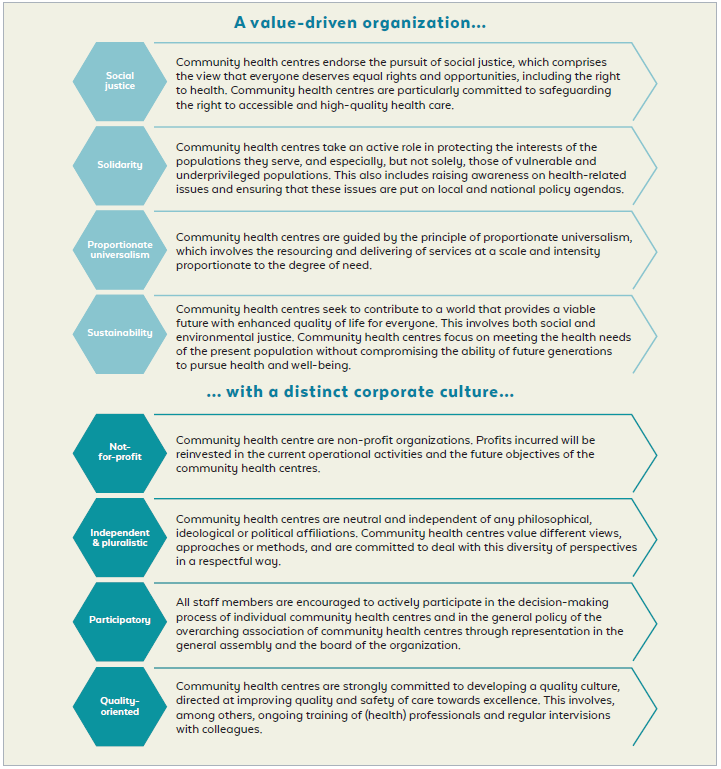

Employees follow the principle of proportional universalism: an equal commitment for everyone (universalism), but where necessary it can be adapted to the needs of the individuals (proportional).

Therefore, the objective is to try to work in a tailor-made way for everyone who registers in the practice. Proportionally, the effort will be greatest for people who are most vulnerable.

The central building block of CHC Botermarkt is that delivering comprehensive primary care services that are person-centred, integral, integrated, continuous and high quality. As the health of an individual and of the community go hand in hand, CHC Botermarkt contributes to a healthy living environment in the neighbourhood as a precondition for healthy behaviour.

With 43 years of the presence in the community, CHC Botermarkt offers an interprofessional team to listen and learn from the community and to strengthen resilience. Importantly, there is a team focusing on health promotion with a ‘health promotion officer’. The centre pays special attention to people with multimorbidity, starting from the patient’s life goals. This is used as the basis for designing a range of subsequent services and interventions by the broader care team that will meet patients’ specific needs.

CHC Nieuw Gent

CHC Nieuw Gent was founded in 2000 under the impetus of the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care of Ghent University. It has 31 full-time equivalents (42 employees) and serves circa 4400 patients, with the potential to add 500 patients within the current capacity.

The specificity of the area for Nieuw Gent is that more than 50% of the housing is social housing. Due to the poor condition of the housing blocks from the 1960s, buildings are taken down en rebuilt, which results in the negative migration saldo.

Apart from the staff and specialists listed in the definition of the CHC (nurses, family physicians, social workers, physiotherapists), there is also a psychologist and pedologist and a dietician that were hired in response to the need in the Nieuw Gent community.

Part of the team is a care coordinator — a person who is responsible for cooperation between all professionals and disciplines. That person is organizing meetings, creating agendas, make sure that cases are being discussed, including complex patient cases, to develop a common vision and common strategy and to facilitate goal-oriented care. Currently, also the prevention and so-called lifestyle medicine is being discussed during those meeting as well — the need of people improving their habits — sleeping, moving, healthy eating, and having a healthy mind.

It took some time for the care coordinators to facilitate learning from each other, build trust and mutual understanding and appreciation of roles and responsibilities.

All team members are implementing goal-oriented care15 by being engaged in developing so called a “chronic care plan”. This label is used to describe a process involving the patient, which consists of a conversation and the co-creation of a care plan, as well as a consultation within the health care team. The patients for whom care plans were created were initially those in a chronic and/or complex (medical or social) situation, with a limited or absent social network, involving multiple care providers and/or in which the care providers involved have a sense of being “stuck”. Patients with these characteristics generally perceive structuring the care provided by the team and sharing of information as a very meaningful exercise.

An in-depth conversation takes place with the patient with the aim of creating an ICF (International Classification of Functioning) “photo” and finding out the patient’s (and the informal carer’s) health care goals. The health care provider can be from any discipline, and a trusting relationship is more important than a medical or paramedical background. This is because goal-oriented care uses a universal language that is spoken by all health disciplines and used with patients and their informal carers. The care team consultation is used to finalise the care plan and set out a number of specific interventions for the members of the health care team. The care plan is included in the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and used as a reference resource. The care team plans the follow-up.

The health and social issues in the community based on 2-year research (including a sample of the population, data from EMRs (in a GDPR proof way), employees, people well connected in the community, such as shopkeeper, pharmacist, social welfare worker, plus data from health insurance companies, in collaboration with the University of Louvain, so broad qualitative and quantitative research) by the team of CHC Nieuw Gent are:

— Acute infectious diseases

— Problems of the musculoskeletal system

— Chronic diseases: hypertension, obesity, sleep disorders

— Social problems

— HIV, schizophrenia, and psychosis

— More chronic cardiovascular risk factors at a younger age

— Dental problems

— Higher incidence of allergenic rhinitis and asthma

— Limited capacities (mental & physical)

— Poverty

— Limited social network

— Cultural diversity

— Housing problems

— Lack of safety

Based on the issues several initiatives were launched, such as:

— Low threshold physical exercise lessons

— Cycling Lessons

— Advocacy meetings re. a mold problem in social housing

— Dental awareness campaign

— Info sessions to stop smoking

— Informing people and signalling/advocacy meetings on urban development and projects in the neighbourhood

— Social artistic project on wellbeing and life goals

— Symposium on the health needs assessment

— Mediation between the social housing companies and tenants regarding bed bugs problem

The main challenges to tackle nowadays are:

— How to have an impact on broader health determinants, such as low income, poor housing conditions?

— How to successfully address policymakers through advocacy and information on problems?

— How to increase networking and collective actions?

— How to better inform and empower the population?

— Setting up boundaries for the CHC role and level on engagement and resources spent in solving a particular issue (especially regarding issues that are not perceived as health-related by the stakeholders — housing, poverty, urban planning, etc.)