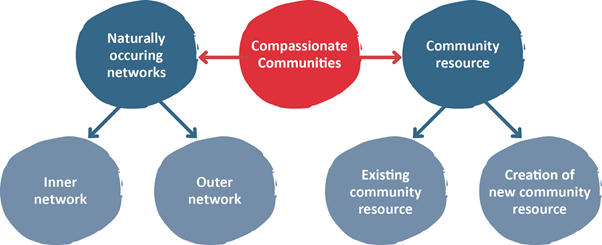

The easiest way to conceptualise Compassionate Communities is to think about them in terms of two major components. The first is the naturally occurring supportive network that surround all of us. If we think about the people who are really close to us, we might count up to anywhere between two and 20, or even 50 people, depending on our life circumstances and our personalities. Our inner network will include family members, friends, neighbours or workplace colleagues. Our outer network is made up of people who we may count as friends or acquaintances and interact with informally. When we start to add up the numbers of people who make up our outer networks, this might be anything from 10 to 200 people or more.

The second component of Compassionate Communities is made up of the communities we live in. It consists of people we do not know directly but nevertheless surround us. We may identify these as a workplace community, a religious community, a sports club, schools, institutions and others within and beyond our neighbourhoods. These communities already exist. We do not need to create them.

Creation of new community resources (assets) comes from both listening to the community to see what is needed as well as making specific suggestions to meet identified needs. These are resources that are particularly useful to help meet the demands of caring for those who are undergoing the experiences of death, dying, loss and caregiving. It is vitally important to ensure that the principles of participatory development are used when building new community resources and capacities. Community development is best done by the community itself, rather than it being something done to a community. In addition, it is also important to make sure that dependency on professional services and finances is not built into anything that is started. If this happens, when the professional support or finances disappear, so does the community resource.

On the other hand, professional services can benefit substantially from embracing a Compassionate Communities (CC) approach. Bringing CC into routine clinical care expands the range of help that clinicians can give by connecting patients to the supportive network and services. The two major areas where clinicians can bring this into routine consultations are network enhancement and linkage to community resource through the use of a service directory.

Compassionate communities consist of naturally occurring supportive networks combined with the wealth of community resource to be found in neighbourhoods, workplaces, educational institutions or any place where people gather. Enhancing the compassionate activities of these groups and networks is an intentional act that is part of a compassionate community programme. Activating these communities can bring immense benefit to the people involved, both those receiving and giving support. Professional health and social care services can work in union and harmony with compassionate communities. If they do so, they will have an enormous resource which will help the people they serve in ways not possible for professional services alone.

Compassionate Cities – dedicated to creating Compassionate Communities

Compassionate Cities are specific communities bounded by city borders and its governance bodies that publicly encourage, facilitate, support and celebrate care for one another during life’s most testing moments and experiences, especially those pertaining to life-threatening and life-limiting illness, chronic disability, frail ageing and dementia, grief and bereavement, and the trials and burdens of long-term care. Though local government always strives to maintain and strengthen quality services for the most fragile and vulnerable, serious personal crises of illness, dying, death and loss may happen to anyone at any time during the normal course our lives. A compassionate city is a community that recognizes and addresses this. While Compassionate Communities focus mostly on neighbourhoods, Compassionate Cities tend to be densely-populated urban organisations with complex and interlocking social sectors. Compassionate cities range from populations in the tens of thousands to those over one million in size and they employ different models of social organisation but all of them have a ‘steering committee’– a central body of people who meet on a regular basis to discuss plans to make their city an active contributor and participant in end of life care.

Compassionate Communities draw from the Compassionate City Charter, which describes 13 social changes to the key institutions and activities of cities to create a city which “publicly encourages, facilitates, supports and celebrates care for one another during life’s most testing moments and experiences, especially those pertaining to life-threatening and life-limiting illness, chronic disability, frail ageing and dementia, grief and bereavement, and the trials and burdens of long term care.”