What is resilience of health systems?

The Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment Resources provides a definition of resilience that emphasizes the importance of the transformational capacity of the health system [1]:

“Health system resilience describes the capacity of a health system to proactively foresee, absorb and adapt to shocks and structural changes in a way that allows it to sustain required operations; resume optimal performance as quickly as possible; transform its structure and functions to strengthen the system; and (possibly) reduce its vulnerability to similar shocks and structural changes in the future”.

Increasing resilience requires transformation of the health system to ensure that the system functions optimally in the long term.

A conceptual framework

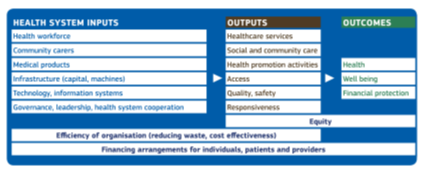

The Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH) developed a Multi-dimensional Health and Social Care Systems (MHSCS) Conceptual Framework.[2]. This framework uses an inputs-outputs-outcomes structure to illustrate the relationships among key elements that contribute towards viable and resilient health systems that support the Sustainable Development Goals. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multi-dimensional Health and Social Care Systems (MHSCS) Conceptual Framework

Can the Primary Care Zone (PCZ) in Ghent be described as a Multi-dimensional Health and Social Care System?

Primary Care Zones (PCZs) have been developed since 2019 in Flanders (Belgium) and were officially established by the Flemish Regional Government on July 1, 2020. They act at the meso-level [3] in the health and welfare system and coordinate and support services in primary health and social care, focusing on prevention, health promotion, care and cure, and on rehabilitative and palliative approaches. The “Care Council” is their governing body. It brings together professionals from health (including mental health) and social care, patient representatives and informal caregivers, as well as local authorities. The health system inputs considered by the PCZ are accessibility, quantity, diversity and quality of the health and social care workforce and of community carers; availability and affordability of medication (role of community pharmacists), and the primary care infrastructure. The PCZ encourages the development of more integrated interprofessional information systems, and provides governance, leadership and cooperation with other levels of the health and welfare system (e.g. hospitals and specialized mental health services). Acute and chronic care services and health promotion and prevention bodies provide the outputs defined in Figure 1, starting with Equity as the overarching principle and addressing upstream causes of ill health and poor wellbeing (e.g. social and ecological determinants) through participative inter-sectoral action for health.

An analysis of the resilience of Ghent’s Primary Care Zone in its reaction to the Covid-19 crisis, based on the 7 effectiveness principles of Integrated Community Care

We examine the actions of the Ghent PCZ (covering 250,000 inhabitants) in response to Covid-19 using the principles of Integrated Community Care. This creates insights into the resilience of the PCZ, and also provides feedback on the validity of the ICC principles in the face of a pandemic. The ICC approach [4] is characterized by the following aims:

CO-DEVELOP HEALTH AND WELLBEING, ENABLE PARTICIPATION

- “Value and foster the capacities of all actors, including citizens, in the community to become change agents and co-produce health and wellbeing. This requires the active involvement of all actors, with extra sensitivity to the most vulnerable ones”. Shortly after the onset of the pandemic, the Ghent PCZ launched an interprofessional and intersectoral Covid-19 team to address the impact, in particular the rising morbidity and mortality rates in Ghent. During the initial stages of the pandemic response, there was a lack of personal protective equipment and testing capacity. Hence, diagnosis was only possible in hospitals and patients had to be referred in order to receive a diagnosis, leading to overwhelming pressure on capacity in terms of both hospital beds and ICU beds (in the first two weeks – thanks to a tremendous effort by the hospitals – the number of ICU beds in the country increased by over 30%). Despite an initial lack of preparedness, the public engaged in ‘social distancing’ measures and initiatives were taken to produce masks within Belgium from the beginning of the pandemic. Outreach to vulnerable groups, such as those experiencing homelessness, provided support, but in many cases their living conditions were not adequate to maintain isolation and quarantine. Although the directors of nursing homes for the elderly were involved in the Covid-19 team from the outset and nursing homes went into lockdown at the start of the pandemic, a large number of Covid-19 infections in nursing homes did occur, leading to over 50% of the total deaths in Belgium. In retrospect, the PCZ did make a difference and was successful in working with all actors to address the pandemic, but was unable to avoid a high level of mortality in vulnerable groups.

- “Foster the creation of local alliances among all actors involved in the production of health and wellbeing in the community. Develop a shared vision and common goals. Actively strive for balanced power relations and mutual trust within these alliances”. The pandemic started before the formal kick-off of the PCZ in Ghent. However, the long-standing collaboration between health and social care organisations in Ghent and the fact that shared goals were formulated for the PCZ, facilitated this intersectoral cooperation. The degree of mutual trust between the actors was variable, but the sense of urgency helped in overcoming differences among organisations. The long tradition of cooperation with local authorities helped to ensure productive interactions between care providers, civil servants and politicians.

- “Strengthen community-oriented primary care that strengthens people’s capabilities to maintain health and/or to live in the community with complex, chronic conditions. Take people’s life goals as the starting point to define desired outcomes of care and support”. One of the most important challenges to overcome in this pandemic was the shift from a perspective of care for the individual towards a perspective that was focused on maintaining and restoring the health of the population. The combined impact of social and ecological determinants of health became obvious and was illustrated in the re-framing of the ‘pandemic’ as a ‘syndemic’[5].

BUILD RESILIENT COMMUNITIES

- “Improve the health of the population and reduce health disparities by addressing the social, economic and environmental determinants of health in the community and investing in prevention and health promotion”.

- “Support healthy and inclusive communities by providing opportunities to bring people together and by investing in both social care and social infrastructure”.

- “Develop the legal and financial conditions to enable the co-creation of care and support at community level”.

Looking at this cluster of three principles, we saw that the efforts made by the city of Ghent to build a supportive community, with investment in social care and social infrastructure over more than two decades, together with the actions of social profit organizations, paid off in the creation of coordinated responses for those most in need. Integrated interventions to bring about improvements in physical and mental health problems increased the resilience of both professional and informal health and welfare sectors. The vaccination campaign, which built on the principle of “equitable allocation of vaccines” put into practice two World Health Organisation principles: “Everyone counts” and “leave no one behind”.

Nevertheless, there are topics that need improvement: the coordination between the level of the Primary Care Zone and the regional and national level (Flanders, Belgium), was not optimal. Especially an integrated strategy for testing, contact tracing, isolation and quarantine was lacking, mainly because of the central hesitation to engage in a decentralised strategy, supported by availability of accurate data and fully taking advantage of the trust of local people in the primary care providers. It took more than 6 months before a functional decentralized approach could be put in place and a real comprehensive data-system is still “under construction”.

MONITOR, EVALUATE AND ADAPT

7. ” Evaluate continuously the quality of care and support, and monitor the status of health and wellbeing in the community, by using methods and indicators which are grounded within the foregoing principles, and documented by participatory ‘community diagnosis’ involving all stakeholders. Provide opportunities for joint learning. Adapt policies, services, and activities in accordance with the evaluation outcomes”.

A local data system, created at the city level, provided a dashboard enabling daily monitoring of numbers of new infections and their geographical distribution. Quantitative and qualitative data were gathered to illustrate the impact of the pandemic on mental health. Initiatives were taken to strengthen mental health services focusing on individuals and groups. The Flemish Institute for Primary Care provided a learning platform for sharing experiences between the 60 PCZs in Flanders. Paradoxically, the experience of the pandemic positively influenced the development and impact of the PCZs in Flanders.

Lessons learned about ICC in the Covid-19 pandemic experience at the meso level

The ICC principles are valid even in the context of a crisis and they contributed to increased resilience[1] at the meso-level in taking care of the population in the Ghent PCZ during the Covid-19 pandemic. There is a need, however, for a greater focus on the issue of preparedness in order to enable the practice of ICC, as we also saw during this pandemic. Certain health system inputs, such as medical products (personal protective equipment, availability of testing, medications and vaccines), infrastructure (quarantine and vaccination centres) and technology (e.g. information systems), are essential in order to put ICC into practice, particularly in a crisis (see figure 1). The creation of a learning community in which we assess the contribution of ICC in developing resilient health systems as described in the introduction, and explore ways to test this resilience in the context of a crisis or structural changes in the future, could be a relevant exercise[2].

References

- EU Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment (HSPA). Assessing the resilience of health systems in Europe: an overview of the theory, current practice and strategies for improvement. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU, 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/systems_performance_assessment/docs/2020_resilience_en.pdf

- Expert Panel on effective ways of investing in health (EXPH), The organisation of resilient health and social care following the COVID-19 pandemic, 25 November 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/expert_panel/docs/026_health_socialcare_covid19_en.pdf

- Creating 21st century primary care in Flanders and beyond. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- Philippe Vandenbroeck, Tom Braes (shiftN). Integrated Community Care 4all New Principles for Care Strategy paper to move ICC forward. Transnational Forum on Integrated Community Care, March 2020.

- Horton R. Offline: Covid-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet 2020;396:874.